Jeannie Moberly

I don’t really make portraits, but I’m excited to do this project. Immediately I think of the only other one I’ve done, when I was 26, in watercolor.

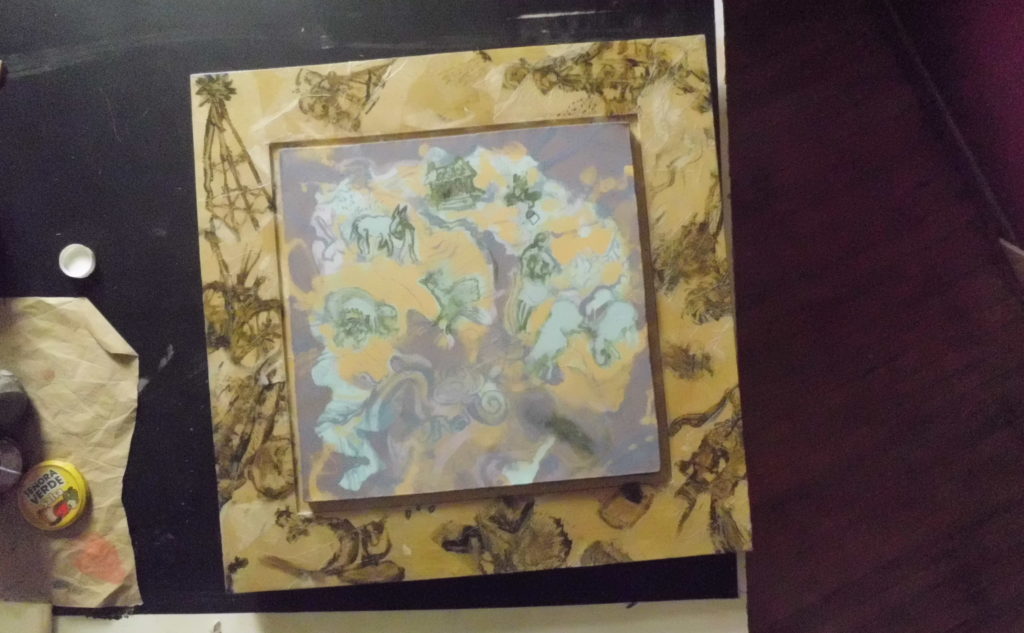

An image comes to mind: a square painting of just my face. In my alley, amidst a pile of old furniture, I see a frame. Well, it’s not a frame—it’s the top of an old table that probably had inset glass—but I see it as a frame. I almost go get it, but I hold back. I’m back in the alley after it rains, and I see the frame is still out there, so I get it. It’s even nicer up close. Vintage, veneer-covered, real wood, beautiful mitered corners. You don’t see that stuff anymore. It’s a bit damaged, and the veneer is peeling in a few places, but I think I can do something with it. “This is a good starting place,” I say.

An image comes to mind: a square painting of just my face. In my alley, amidst a pile of old furniture, I see a frame. Well, it’s not a frame—it’s the top of an old table that probably had inset glass—but I see it as a frame. I almost go get it, but I hold back. I’m back in the alley after it rains, and I see the frame is still out there, so I get it. It’s even nicer up close. Vintage, veneer-covered, real wood, beautiful mitered corners. You don’t see that stuff anymore. It’s a bit damaged, and the veneer is peeling in a few places, but I think I can do something with it. “This is a good starting place,” I say.

I work in fits and starts, just a couple minutes here and there. I’m working on other projects at the same time. It’s just how I do things: in stolen moments, stolen from myself. And it’s like my workspaces are stolen too, because everywhere in my house is crowded with all sorts of junk I’m always working against, and working on. I think of myself as a bug with a lot of legs, each leg doing something else. It’s kind of an ugly picture of myself, thinking all I do is run around working. I’m not sure that’s really the appropriate way to live, but I can’t help it: I’m a bug.

As the days pass I think from time to time how to use the frame. The opening is 16 inches square. I plan to fit a piece of masonite board inside and paint on that. The frame itself is about an inch deep, so I may carve a relief. That really strikes me as a possibility. But it would be difficult, and I might just want to be more relaxed with this, not developing new techniques.

And I think too about how to depict myself. I’m thinking of myself more and more as a kind of brain. There’s so much to me that just the face wouldn’t show. I am so much—I don’t even know what’s down deep. And so much of my existence is what’s on the border. I can’t even identify myself without thinking about the interface between inside and outside. I’m pulled by the outside world, and I have to deal with the outside world, and I am not even possible without what’s outside me. So this will be an exploration.

What keeps coming to mind, as an example of this inside/outside thing, is my sister’s farm. It was always my mother’s dream to live on a farm. She thought it was something to get back to, while my father saw the farm as something to escape. So here my sister is; she’s moved to an old plantation in the South all by herself with these two dogs, and she needs help. I’m thinking of going down to help her. And I think about how this ties into farming being part of America’s heritage but something that is being lost, more and more but which comes up in politics as the ideal. So part of working on this portrait is me trying to understand the mentality of the person displaced from their farm and the person still living on their farm—that dream of the independent person taking care of themselves, doing things their own way. The only place that’s left is in somebody’s head, pretty much.

This is very enjoyable. It makes me feel like I’m dealing with these issues, my ambivalence about the farm. It all sort of settles, like slowly stirring a pot to keep it from boiling over.

I go to get the masonite ready, and I’m surprised that none of my pieces are big enough. So I decide I’ll stretch a canvas instead, on my trademark redwood stretchers and with some old material from my last sewing job.

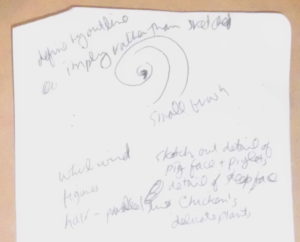

It’s time to do some sketches. I’ll do them in multiple sizes, starting small and working up to a full-size 16-by-16 sketch. Sorting through my paper, I come across some really nice vellum scraps, so I decide to use them. The first piece I take, I draw my face in green chalk. I cut the edges to make the face more tilted and off-center, more what I’m going for. I’m an unbalanced person, and I want to show that. Now I draw the brain on the head, and the farm will be in the brain. Again, I’m just working a few minutes here and there. A lot of my time is spent just looking. The next thing I do is cut off the chin a little bit, and then I redefine the face in pencil. I want the brain open at the top, so the sky of the outer reality and the farm will be continuous. Next I think about what will go in the farm. I do little sketches, not using any reference: chickens, pigs, sheep. I don’t use any references, because I don’t care about realism. This is a farm in the brain; it doesn’t have to be realistic. I put these sketches up on a drawing board, and arranging them helps me visualize the final composition. Another thing I do with the vellum is cut a piece into the shape of a brain and lay it on the canvas. It wasn’t big enough at first so I added another piece behind it. That will be the lizard brain. Then I didn’t like the front, so I ripped it and expanded it outward. All this helps me visualize the finished piece. The plan is to make full-size sketches of the general forms and arrange these smaller pieces onto that sketch, which will then be transferred onto the painting.

It’s time to do some sketches. I’ll do them in multiple sizes, starting small and working up to a full-size 16-by-16 sketch. Sorting through my paper, I come across some really nice vellum scraps, so I decide to use them. The first piece I take, I draw my face in green chalk. I cut the edges to make the face more tilted and off-center, more what I’m going for. I’m an unbalanced person, and I want to show that. Now I draw the brain on the head, and the farm will be in the brain. Again, I’m just working a few minutes here and there. A lot of my time is spent just looking. The next thing I do is cut off the chin a little bit, and then I redefine the face in pencil. I want the brain open at the top, so the sky of the outer reality and the farm will be continuous. Next I think about what will go in the farm. I do little sketches, not using any reference: chickens, pigs, sheep. I don’t use any references, because I don’t care about realism. This is a farm in the brain; it doesn’t have to be realistic. I put these sketches up on a drawing board, and arranging them helps me visualize the final composition. Another thing I do with the vellum is cut a piece into the shape of a brain and lay it on the canvas. It wasn’t big enough at first so I added another piece behind it. That will be the lizard brain. Then I didn’t like the front, so I ripped it and expanded it outward. All this helps me visualize the finished piece. The plan is to make full-size sketches of the general forms and arrange these smaller pieces onto that sketch, which will then be transferred onto the painting.

Now I know what I’ll do with the frame. I’m going to decoupage some sketches onto it, to keep thinking about this inside/outside idea. I’ve been thinking about the farm machines my granddad had. When I was a kid, my family went to live on his farm for a while when my dad was out of work. My grandfather took me and my little sister on walks. I think he had 100 acres. And he had all these farm machines rusted solid in the field, beautiful things, huge. It was this industrial machinery, but it was totally useless. I was amazed. I loved it. It was fun to climb on. And as I got older, I can’t help but think of that machinery from time to time. It strikes me: You try to create some utopian way of doing things, and it winds up as garbage sitting out forever. In civilization there are so many things we’re able to do, but can we clean up the mess it makes? Why can’t we take care of the things we have? I think of the plumbing, the roads, all the infrastructure in this country is crumbling and it’s just like that farm machinery.

Now I know what I’ll do with the frame. I’m going to decoupage some sketches onto it, to keep thinking about this inside/outside idea. I’ve been thinking about the farm machines my granddad had. When I was a kid, my family went to live on his farm for a while when my dad was out of work. My grandfather took me and my little sister on walks. I think he had 100 acres. And he had all these farm machines rusted solid in the field, beautiful things, huge. It was this industrial machinery, but it was totally useless. I was amazed. I loved it. It was fun to climb on. And as I got older, I can’t help but think of that machinery from time to time. It strikes me: You try to create some utopian way of doing things, and it winds up as garbage sitting out forever. In civilization there are so many things we’re able to do, but can we clean up the mess it makes? Why can’t we take care of the things we have? I think of the plumbing, the roads, all the infrastructure in this country is crumbling and it’s just like that farm machinery.

So I have the image in my mind of the farm machines, and the amazing thing is nowadays I can go online and look up “vintage farm machinery,” and sure enough, I find them: combine harvester, hay-bailer, other ones whose names I don’t know. And I draw them. I don’t have a printer anymore, so I draw straight from the screen. The internet makes it so easy now. In the past this would have taken many hours at the library, and many intermediate sketches. As I continue working out the machinery, I refer to a book I have, How Things Work. I’ve always loved this book. It has all kinds of diagrams of gears and pulleys, and I page through it for a while to get a sense of these machines. I want my farm machines to have a mechanistic impression, just to give a general feeling. As I page through, I’m constantly thinking: How can I make this part of what I’m doing?

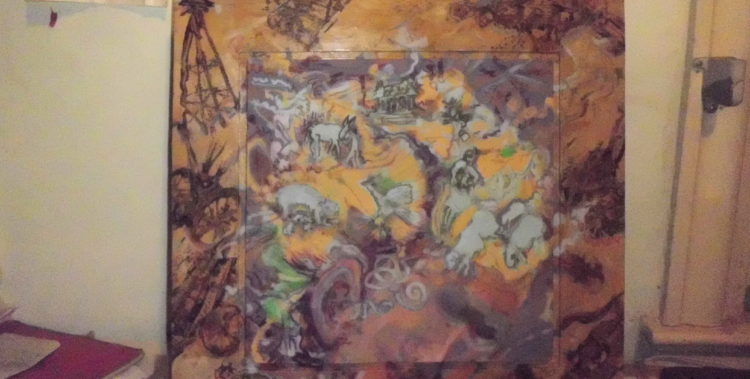

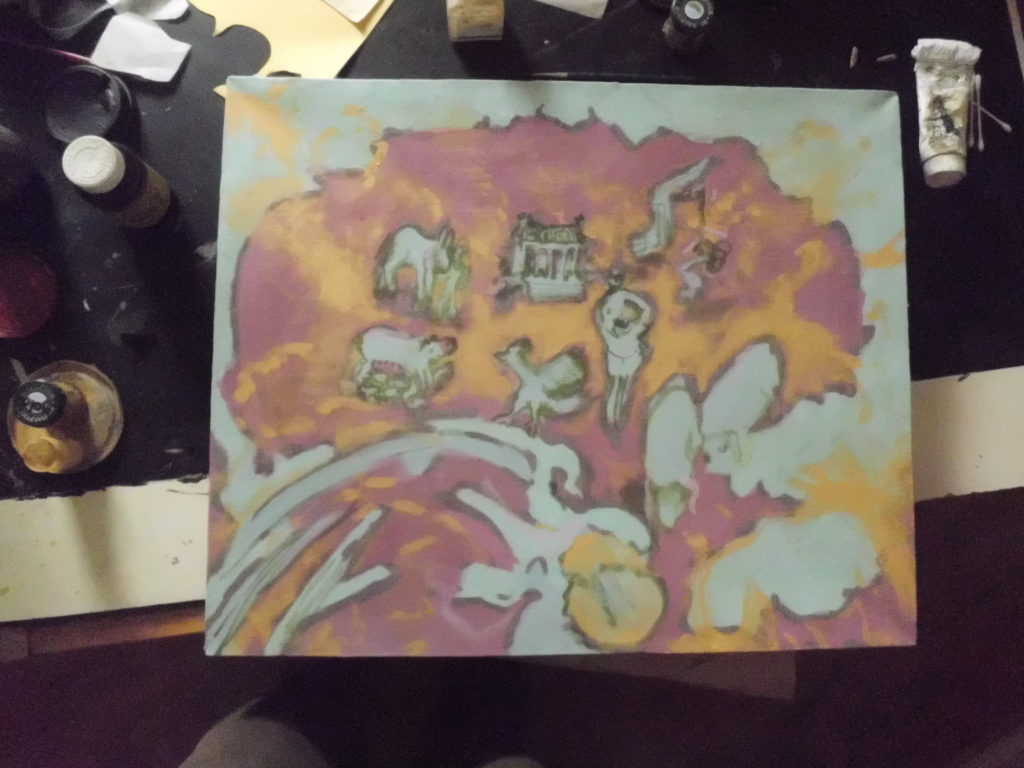

Now that all the elements are in place, it’s just bringing everything together. I feel rushed, like my subconscious is eager to get onto other things, but this takes time. A few days later I’m ready to gesso the canvas. I’m going to use multiple colors to contrast the different elements of the image—the brain, the farm, the background. To transfer the sketches to the canvas, I make stencils out of them using ripped paper, and I paint over these. I realize I want to make another painting, one of just the farm, so I reuse these stencils on a second canvas.

As for the gesso and paint, I use the same ones that I’ve mixed for other pieces I’m working on; as always I’m doing several simultaneously. I rough in the brain and the face in gesso, and it reminds me of Bob Dylan’s album where he’s got that afro hairdo. I’ll need to keep working out the details of these things as I progress, but I’m happy for now. I decide I need a foreground element to break up the reddish color, so I paint in a daffodil over where my face will be. I go on the computer and pull up an image, and I do a two-minute painting of it. Now I feel this painting has reached the top of a hill. It was hard to get here, but now I can see how things are. My vision of the finished piece is much clearer. Finally having paint on the canvases makes me feel like they’re almost done.

In subsequent sessions I add darker colors for detail. I’m working on my self-portrait and the farm painting simultaneously. When I need to figure out how one of the farm elements should look, I work it out on the farm painting first and then do it on the self-portrait. Next is an orange-yellow, which is so bright that it needs to be used sparingly. As I paint, I wonder how far I should go, pushing against some invisible borders. But I go beyond that border, and I feel it, and the yellow is like a path that goes out in all directions from my brain, connecting the internal and external, even onto the frame.

Then I meet one weekend with a discussion group on motion, and we’re talking about the inner ear and its role in balance. That gets me thinking. All my life I’ve had motion sickness. And my imbalance is visible in the painting, with my tilted head, and how the ear is right there in the center. I look up photos of the inner ear to do a sketch, and then I draw my own ear in the mirror. I use a blue-gray paint that I mixed for another piece. I feel great about this, letting the inner ear coming into focus and leaving the brain blurrier, because I realize that carsickness and motion sickness has been such a driving force in my life. I think it was why I hated grade school (when I had to take the bus) and excelled in high school (when I could walk), and I even think it’s why I’m an atheist (because we drove to church on Sundays, sometimes twice, often followed by a Sunday afternoon drive).

Then I meet one weekend with a discussion group on motion, and we’re talking about the inner ear and its role in balance. That gets me thinking. All my life I’ve had motion sickness. And my imbalance is visible in the painting, with my tilted head, and how the ear is right there in the center. I look up photos of the inner ear to do a sketch, and then I draw my own ear in the mirror. I use a blue-gray paint that I mixed for another piece. I feel great about this, letting the inner ear coming into focus and leaving the brain blurrier, because I realize that carsickness and motion sickness has been such a driving force in my life. I think it was why I hated grade school (when I had to take the bus) and excelled in high school (when I could walk), and I even think it’s why I’m an atheist (because we drove to church on Sundays, sometimes twice, often followed by a Sunday afternoon drive).

The blue-gray is such a great color, but I don’t want to overdo it. I prefer to not put too much paint on there—I always want it to be perfect the first time, a nice crisp line, rather than trying to fix it. Fixing it always ruins it. In the end, I think I do overdo it a bit. Part of the problem is my brush, which I’m not satisfied with because it’s long and floppy and I’d rather have a stiffer, more precise brush. I go to my farm painting and try to put some of the blue on there. I get two lines in and it stops me. I just can’t continue. I need to put it aside for a while. I know I like the blue on there but I don’t know how to use it yet.

In the following days, I resolve the blue and move on to some pink. At some point I decide to stop working on the farm painting. “This is all too much for me,” I tell myself. But once I mix up the blue, I find myself thinking, “Yeah, the farm needs some blue, too.” So I bring that canvas back out and put some blue on it. They’re kind of a conjoined pair, so what can I do?

Amidst this, we have a terrible plumbing disaster in my house. Things are a mess right now, but I have time to paint because this and that has to be settled on the house before I can continue fixing the bathrooms. Beyond just this, my summer hasn’t turned out as I’d hoped. It’s been very stressful, not a happy time. So I see in my painting a little of myself as this person in the world. Though it’s not as angry as this other piece I’m working on now, which is kind of a raging feminist thing. Interactions in the world, they just have been wearing me down.

Amidst this, we have a terrible plumbing disaster in my house. Things are a mess right now, but I have time to paint because this and that has to be settled on the house before I can continue fixing the bathrooms. Beyond just this, my summer hasn’t turned out as I’d hoped. It’s been very stressful, not a happy time. So I see in my painting a little of myself as this person in the world. Though it’s not as angry as this other piece I’m working on now, which is kind of a raging feminist thing. Interactions in the world, they just have been wearing me down.

Another day, I work on the painting four little times. Purple for an hour and a half, and then pink a few other times. What I’m doing is trying to create a path for the eye, to keep the eye moving, and if the eye ever gets caught somewhere, it needs something. It takes letting time pass. At 1:30 in the morning, when I am supposed to be doing something else, I sneak back in and put on a tiny daub of pink paint, and now the thing is finished.

This story was written by Tim Gorichanaz based on interviews with Jeannie Moberly. You can learn more about Jeannie on her website.